Join my newsletter for my free eBook 5 STEPS TO CREATE AND MAINTAIN YOUR WRITING SCHEDULE.

When I meet writers, whether emerging or established, I ask them the same ice-breaking question: What do they find to be the hardest thing about being a writer?

The most common answer is finding time to write.

I’m not surprised, because finding time to write is impossible. What surprises me is that writers even bother trying to find time to write.

The answer suggests that writers don’t understand time, and don’t understand the basics of self-management. They may know how to write, but they don’t know how to work. They overlook or discount basic strategies — even though they might use these same strategies, with exceptional results, in other areas of their lives.

“Finding” Time to Write

There is one way to “find” time to write: Look at a calendar, and decide what day you will write, and what time. In other words, you cannot find time, and time will not magically appear. You can only allocate your time, in advance.

Similarly, there is one way to be a productive writer: Write according to a schedule.

The Importance of Your Schedule

Writers that resist scheduling writing time have many excuses. In his excellent book How to Write a Lot, psychologist Paul J. Silvia labels these excuses “specious barriers.” He identifies and refutes the most common of these specious barriers to writing, the first being trying to find time to write:

Why is this barrier specious? The key lies in the word find. When people endorse this specious barrier, I imagine them roaming through their schedules like naturalists in search of Time To Write, that most elusive and secretive of creatures. Do you need to “find time to teach”? Of course not — you have a teaching schedule, and you never miss it. […] Finding time is a destructive way of thinking about writing. Never say this again. (12)

Silvia’s book is aimed at academic writers (which is why he assumes that his readers are also teachers), but everything in the first half of the book applies equally to creative writers (who are often also teachers). Even if you aren’t a teacher, you routinely schedule things that aren’t writing, and you stick to your schedule — unless you simply have no control over your life (in which case, writing is the least of your problems).

A barrier that Silvia doesn’t address fully, but which people often bring up when talking to me, is the anxiety that attends the act of writing. Many writers I know (myself included — I’ve been there) feel guilty about not writing but also anxious about writing. The less they write, the more guilty and anxious they feel. When they do write, finally, they often do so in binges (usually before a deadline), and the experience is horrible due to the pressure of the deadline.

Yet they succeed (sometimes), turning in their writing by the deadline. Perhaps they aren’t proud of the work produced under this pressure, and negatively reinforce their own anxieties about writing. Perhaps they are proud of this work — thus positively reinforcing their bad habits. Either way, these writers reinforce their assumptions about themselves and their writing: (1) they work best when they binge-write, (2) they aren’t capable of keeping a schedule, (3) their anxiety about writing is uncontrollable or perhaps even necessary to their art.

All of which is nonsense. Silvia — a psychologist, remember — addresses the issue adequately in a little over a page:

Binge writers spend more time feeling guilty and anxious about not writing than schedule followers spend writing. When you follow a schedule, you no longer worry about not writing, complain about not finding time to write, or indulge in fantasies about how much you’ll write over the summer. Instead, you write during your allotted times and then forget about it. We have better things to worry about than writing. […]

When confronted with their fruitless ways, binge writers often proffer a self-defeating dispositional attribution: “I’m just not the kind of person who’s good at making a schedule and sticking to it.” This is nonsense, of course. People like dispositional explanations when they don’t want to change (Jellison, 1993). People who claim that they’re “not the scheduling kind of person” are masterly schedulers at other times: They always teach at the same time, go to bed at the same time, watch their favorite TV shows at the same time, and so on. I’ve met people who jogged at the same daily time, regardless of snow or rain, but claimed that they didn’t have the willpower to stick to a daily writing schedule. Don’t quit before you start — making a schedule is the secret to productive writing. If you don’t plan to make a schedule, gently close this book, clean it so it looks brand new, and give it as a gift to a friend who wants to be a better writer. (14-15)

Sometimes, writers resist making a schedule because they don’t have ideas for writing — this is perhaps the most specious barrier of all, since ideas for writing can simply be stolen (à la Shakespeare or Kenneth Goldsmith) or manufactured by force (as any writing exercise will prove). Nevertheless, some writers persist in the mistaken belief that they must wait for inspiration, even though:

Waiting for Inspiration Doesn’t Work

Most good writers already know this. However, many still cling to the fallacy that inspiration is necessary to produce any writing, or to produce good writing. Silvia points to research by R. Boice, who “gathered a sample of college professors who struggled with writing, and […] randomly assigned them to use different writing strategies” (24).

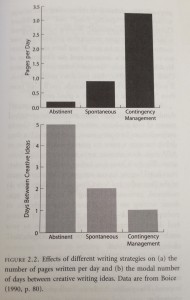

Although “college professors” is a very narrow, limited sample, the results are intriguing and instructive for writers of all stripes. The three writing strategies assigned by Boice were:

- abstinence — writers told not to write at all, “forbidden from all nonemergency writing”

- spontaneous — writers who scheduled 50 writing sessions but did not have to keep them — they could write anytime, and also only had to write during these sessions when they felt inspired — in other words, they could write as much as they wanted, whenever inspiration struck

- contingency management — writers who scheduled 50 writing sessions, were forced to write during each session, and were told not to write outside of these sessions

The results? See for yourself:

The contingency management writers wrote 3.5 as much as the spontaneous writers, and 16 times more than the abstinent writers. Most significantly, writers “who wrote ‘when they felt like it’ were barely more productive than people told not to write at all” (24). In addition, “forcing people to write enhanced their creative ideas for writing” (24):

The typical number of days between creative ideas was merely 1 day for people who were forced to write: it was 2 days for people in the spontaneous condition and 5 days for people in the abstinence condition. Writing breeds good ideas for writing. (24)

I must acknowledge that Silvia does not suggest, anywhere, that the anxiety some associate with writing will lessen during the writing process. Common sense dictates that the more familiar and practiced you become, the less you will feel like an imposter or filled with anxiety, but many writers never let go of these feelings. Writing, in my experience, remains difficult and seems sometimes to be getting more difficult.

Nevertheless, this is irrelevant. The difficulty of writing will of course decrease with practice, but creative writers (ideally) are always working to raise their skills and so taking on tasks of increased difficulty, which from time to time will negate the benefits of practice. The end result? Either writing gets easier, and your skills barely improve, or writing gets harder, but your skills improve substantially.

Regardless, the best way to be productive (with difficulty or without) and to get control of your anxiety about writing is to demystify the process and normalize the activity through repeated exposure.

“The Schedule’s the Thing,” Like Shakespeare Should Have Said

Both Paul J. Silvia and David A. Rasch (another psychologist, this one a specialist on writers who struggle with blocks, procrastination, and related issues) agree that the details of your writing schedule (e.g., when you write, how long you write) are somewhat irrelevant in a general sense. If you have specific goals that require specific time commitments, then it might be a different matter, but generally speaking the important thing for writers is to institute a writing schedule, no matter what that schedule might be.

Silvia puts it this way:

The secret is the regularity, not the number of days or the number of hours. It doesn’t matter if you pick 1 day a week or all 5 weekdays — just find a set of regular times, write them in your weekly planner, and write during those times. To begin, allot a mere 4 hours per week. After you see the astronomical increase in your writing output, you can always add more hours. (13)

Rasch, in The Blocked Writer’s Book of the Dead, takes a more detailed look at the psychological barriers (specious and otherwise) that writers put up to avoid writing. The Blocked Writer’s Book of the Dead is structured like a workbook, and is of more use to writers with severe procrastination issues or other mental blocks that may prevent them from writing. (Ignore its cheesy cover.)

Rasch is less of a tough-love advocate than Silvia, but he still takes a behavioural approach and agrees fundamentally about how to be a productive writer. Here are a few of the things Rasch has to say about writing schedules and related matters:

Many writers with productivity problems have trouble with time. … Every day, through conscious planning or by unconscious default, you prioritize your activities and make decisions about how to spend time. It can be quite a challenge to determine how much time the writing portion of your life requires, and to incorporate that into a workable routine. (18)

I have worked with several writers whose primary challenge was taking the step of sitting down at their desk. Their anticipatory anxiety or other resistances create a mental barrier against taking the first step. Often they are entertaining an inaccurate and exaggerated estimate of the agony that will ensure if they write. (19)

I encourage blocked writers to make failure less likely to occur. For many reasons writing is frequently difficult to do, so respect that reality […] Make changes by taking small steps that would be difficult to not do. For instance, if your goal is to start writing every day, if you make the sessions short (15 minutes) you may find it hard to rationalize skipping the session. I encourage you to be pragmatic and do what works, whether or not it fits your image of what a “real” writer would do. (62)

An advantage of a regular schedule is that it eliminates the daily process of deciding when to write. Each time you have to make a decision about writing, it increases the likelihood that you will decide not to do it. The more regularly you write, the less dreadful it feels to face it each day. To the extent that you generate new, positive associations with writing through regular practice, you reinforce your efforts. (63)

Scheduling writing is not the only way to become more productive, but I have seen it produce powerful results for those blocked writers who found a way to move in this direction. Write daily. Write daily. Write daily. This is the single most important piece of advice in this book. (63)

Here is a nutshell summary of Rasch’s other advice regarding how to make a work schedule (I have simply recorded the subsection headings under “Make a Work Schedule”):

- Write daily

- If work avoidance is a problem, begin with short writing periods

- Choose a time when your energy is good and distractions will be minimal

- Resist the urge to overdo it

- Track your performance

Rasch’s book is worth a read (he even deals with a problem on the other end of the spectrum, writers who write a lot and work long hours, who write often and without much anxiety, yet have little to show for it). He briefly addresses a host of issues, including dealing with criticism, actual psychological disorders like depression and how they might relate to writing, and so forth. Rasch provides a variety of strategies writers can use to be more productive and reduce their anxiety, and also helps the reader identify their actual issues with writing and get a sense of whether or not they might need to be addressed somehow beyond the book.

One simple piece of advice that Rasch offers, which I have found especially useful, is to make a “routine, simple pleasure contingent upon writing first.” I don’t drink coffee except when I write (sometimes I allow myself a coffee after I write; for example, if I want to go to coffee with somebody, then I write first). I appreciate coffee more, and I don’t over-caffeinate, and I write.

My Writing Schedule

I have to keep shifting my writing schedule each term, which is frankly a bad idea. But that’s my reality. I’m no saint, and I will often fail to follow the schedule as rigorously as I should. But I produce a lot of writing and I’ve published five books in the last five years, so I can attest to the fact that even a half-followed schedule will work wonders for you. Here’s mine in a nutshell:

- I write weekdays, not weekends. I take two weeks off every year. (I track the days I take off.) This is, of course, my ideal and not my reality.

- This term, I am writing from 10 – 11 a.m. every weekday. On Tuesdays and Thursdays, this is pretty much all the writing I can do — nestled right between my morning classes. On Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays, I will keep this same start time but then keep writing as long as I can. As of this very minute, it’s a Wednesday, and it’s 12:44 p.m. Right this minute, I’ve written 2270 words today, since 10 a.m.

- I set an alarm for 9:55 (my iPhone plays Elvis Costello’s song “Every Day I Write the Book”). When it goes off, I make coffee, then I start listening to Agalloch, then I start writing.

Your Writing Schedule, and Defending It

What is your writing schedule? Have you had success with a schedule, now or in the past? Have you had problems sticking to a schedule? Let me know.

If you haven’t yet done so, start a schedule. Try it for a week — just 15 minutes each day, as Rasch suggests. See how it goes. You’ll be surprised.

One problem you’ll run up against is people not respecting your schedule. That’s okay. Only you need to respect it. Jealously defend and guard your time. As Silvia puts it, when you start saying “no” to requests that conflict with your writing schedule, you will meet with resistance from others.

That’s life. Refuse anyway. As Silvia puts it, “only bad writers will hold your refusal against you” (16).